Lessons from aerospace on managing time pressures and behaviours in markets.

‘Waste not your Hour, nor in the vain pursuit

of This and That endeavour and dispute;

Better be jocund with the fruitful Grape

Than sadden after none, or bitter, Fruit.’

Omar Khayyam, the twelfth-century Persian poet and scientist, knew that time is finite, limited and all too often wasted. But the perception of time by human beings, far from being a universal constant, can differ in a million or more ways. For some, time is something that rushes forward at an incredible pace, uncontrollable, and with an anxious feeling that it is running out. For others, time has a slower, more nuanced pace that requires respect and must be savoured and understood in ways opposed to those who see time as purely linear and universal.

At the risk of becoming too ethereal, let’s bring it down to our main point. As groups of people, the markets experience their own particular and unique perceptions of time.

Specifically, market participants have different perceptions of time. As individuals, we are aware of the apparent elasticity of time. Our lives are full of anecdotal stories, “time flew by” when in a hurry, “I lost track of time”, or how the day seems more extended and productive when we wake early, etc.

Time awareness, the meaning of time scales, and time pressures can affect how we behave in high-pressure environments such as financial markets, aerospace, government, etc.

Ancieo.Ai’s roots are in aerospace, and in aerospace, we learn how to manage time.

Sounds a bit pompous? Let me explain. When we prepare for emergencies, one of the first elements of any plan is recognising the available time. So we ask ourselves, Is this time-critical? Can we optimise or increase the time available? Knowing that we make better decisions when in control of our own time, we learn to manage it.

These management skills have seen widespread adoption beyond aerospace, particularly within medicine. The use of checklists to prioritise actions within time constraints and simulated emergencies in operating theatres has become standard practice in teams learning to manage time.

Beyond aerospace and other emergency services, there has also been exciting work exploring time perception beyond the individual by delving into their cultural biases and backgrounds. For example, a western individual may perceive time as property, so it feels like it’s ‘theirs’, and therefore they may feel the need to possess their time and become anxious and defensive when they think others are wasting their time. On the other hand, another individual, perhaps someone drawn from a background stemming from a Confucian tradition, may see other people’s time as a gift and something to be valued and treated accordingly, with politeness and gratitude. The converse may be true when individuals from different backgrounds see time limitations, such as punctuality, as less important than the personal interaction and ensuing relationship that evolves.

This may seem like racial bias, but it is not. By discussing awareness of differing cultural perceptions of time and how this may affect our internal decision-making, we become more aware of one’s internal biases and schemata when assessing one’s relationship with time. To understand and optimise one’s decision making, we need to see time as another factor that may pull our cognitive processes in varying directions.

Perception of time, and the management of one’s reaction to time, have a vital role. It can help you mitigate risk.

How do you mitigate risk by adjusting your relationship with time, and how does this affect behaviours and market strategies?

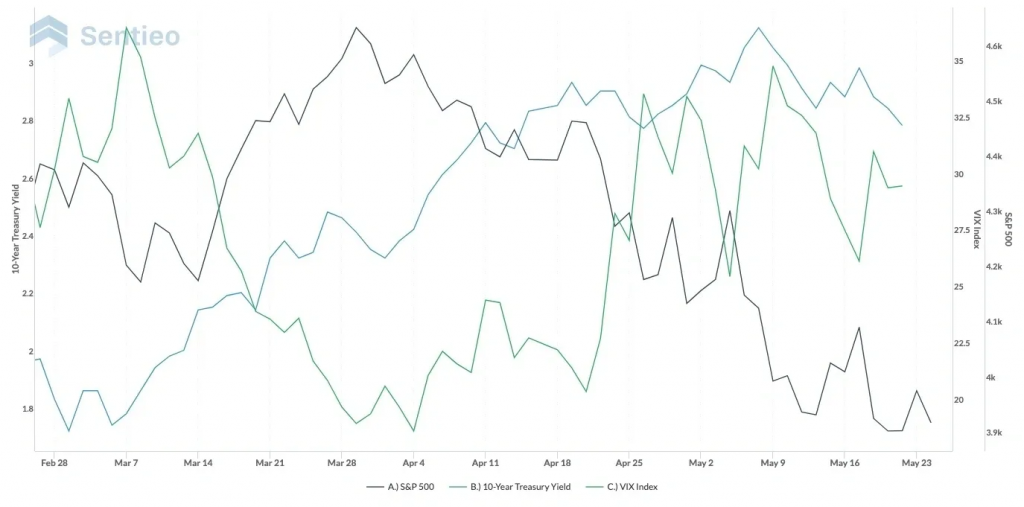

Awareness of time may allow us to see through short term volatility and resist the temptation to overreact to outside stimuli. Again, we aim to look at time as a resource in aerospace. Before making an approach towards an airfield, either at the planning stage or inflight, we ask ourselves how much time we need. We see it as a finite resource (usually by way of fuel and therefore available flying time, which generates options) and as a moving and evolving reality as external and internal conditions change. We aim to match the resource to reality. We aim to seek to optimise our time with the world around us.

Whilst this theory works in aerospace, it also works in investing.

These observations could place us squarely within the scope of behavioural economics and the land of temporal discounting. For those unfamiliar, this particular theory works because humans tend to prefer immediate gratification rather than the potential reward after a more extended period. We may opt for an apparent quick resolution when faced with an unpleasant set of options. This temptation can often be a mistake.

Additionally, anchoring is a behavioural principle whereby we tend to place greater weight on the first piece of information we receive. This cognitive bias is one of the reasons why aerospace emergency procedures place such importance on the review element in a decision-making process. The first piece of information can hide the real meaning behind it.

So how do we deal with these human frailties? In an emergency, the decision process goes something like this:

Fly the aeroplane. This simple statement covers a multitude of essential skills. First off, someone has to be in charge; hence “I have control.” Leadership is a vast subject, not for this article, but the whole thing relies on someone being in control.

Identify the problem; we know something has gone wrong, but what is it? Misdiagnosis or misidentification of an issue can turn an incident into a crisis.

And then come up with a plan. And it’s at this stage that time becomes all-important. Your perception of time and where the incident sits within the actual flow of time will ultimately decide the next course of action.

We’ll discuss the plan and its relevance to time in our following newsletter.