AAM is in trouble, and SPACs could be to blame.

Advanced aerial mobility (AAM) companies are at the leading edge of aerospace technology. They promise to deliver clean, safe and efficient transport from renewable sources as a vital part of the green transition.

But all is not well in the AAM industry, and one of the root causes appears to be the difference in expectations of time and progress between investors and manufacturers. It can’t have escaped anyone’s attention that investors have been having a torrid time this year in just about everything apart from the US dollar.

To quote Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway.

“I don’t think we ever had anything quite as we have now regarding the volumes of pure gambling activity going on daily.”

“It’s not pretty.”

And Evtol/AAM companies have been right in the middle of it.

For example, Lilium (LILM), the German AAM company, has become the subject of a class action under the auspices of the US law firm Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd LLP. The same law firm that became known for working to uncover some fraudulent activities behind the now-defunct energy firm Enron.

Their case largely centres around Lilium’s battery performance claims, held within the investment prospectus and other documents, leading to the SPAC (special purpose acquisition company) transaction between Lilium and Qell acquisition company, a so-called ‘blank cheque company’.

Their action alleges that specific individuals within the executive team at LILM overstated the performance of their battery technologies (vital for an all-electric aircraft) and LILM’s access to proprietary battery technology.

As Lilium is undergoing litigation on this subject, we will not comment on the specifics of their case.

LILM is not alone in being the subject of a class-action suit. After undergoing a merger with a SPAC, Lucid Group (LCID), and Grab Holdings (GRAB) have all suffered class actions, and they won’t be the first or last.

All the complaints follow a similar path, with a complaint that the defendants have overstated elements of their offering. With GRAB, it was driver availability, LCID production capability, and LILM, the primary complaints centre on its technologies.

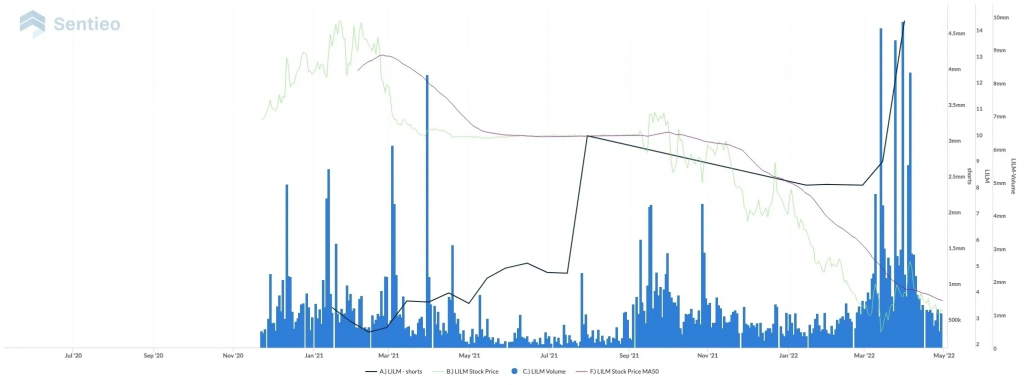

For LILM, the results have been dramatic. Not only are they the subject of a class action, but further complaints have been made to the SEC. Unsurprisingly, LILM has attracted the attention of short-sellers.

Note the short-selling activity post the March 14th report in the chart below.

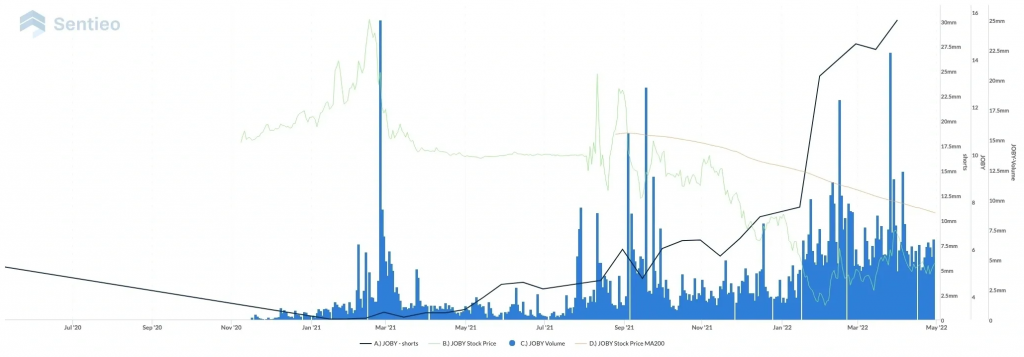

The other major listed Evtol/AAM companies have experienced similar declines and volatility, even without LILM’s current legal obstacles.

Not all of these companies are subject to legal jeopardy, but they are subject to risk. Tangible, quantifiable risk. See below from the LILM F1 form lodged with the US SEC. Laid out in clear prose are just some of the risk factors associated with this (and most) aerospace projects. The flow of aerospace development of new technologies has a pattern.

(From the Lilium F1 form below).

“Risk Factors”

Investing in our securities entails high risk, as more fully described in the “Risk Factors” section beginning on page 13. These risks include, among others, include:

- We have incuJOBY Share price, moving average, shorts and volume.rred significant losses and expect to incur substantial expenses and continuing losses for the foreseeable future, and we may not achieve or maintain profitability.

- The eVTOL market may not continue to develop, or eVTOL aircraft may not be adopted by the transportation market.

- Our eVTOL aircraft may not be certified by transportation and aviation authorities, including EASA or the FAA.

- The Lilium Jet may not deliver the expected reduction in operating costs or time savings that we anticipate.

The central theme of any aerospace project is the need to satisfy the relevant regulators. Without certification and permission, a civil aerospace product will not fly commercially. Let’s make that point again: if a civil aerospace vehicle cannot achieve certification, that’s it until it does.

And perhaps that’s it for good if the technology cannot achieve the compliance necessary to satisfy the regulators.

This is the primary difference between investors in aerospace and those who invest in software or other forms of products and services. You can invest in software as a service, and with the possible exemptions for consumer or contractual laws, there is no genuine regulatory hurdle to cross. This dramatically reduces development risk and costs.

The same cannot be said of investments in aerospace. Investors need to be aware of this hurdle and what this means in their risk assessments and due diligence.

There is another reason to see time and experience spent in development as essential in new hardware technologies, such as AAM. And that reason is Wright’s Law. Theodore Wright, an aeronautical engineer, discovered a predictable improvement in the efficiency and costs of production. With aircraft, Wright found that there would always be a 15% improvement in prices for every doubling of production.

So, if we apply Wright’s Law, those AAM companies that are given the space and time to develop and learn will succeed. They will have the time to learn how to do things better, safer, and cheaper. Wright himself called it “the learning time.”

It’s a well-known phenomenon in aerospace. As engineers, designers and production teams produce aircraft on the production lines, they learn by doing. So aircraft become lighter, stronger, and more efficient as tweaks and modifications are made to later models. This phenomenon is so well known by the markets that aircraft financiers pay a premium for those later-stage airframes.

Investors need to be clear on this. Aerospace isn’t an app. Ask Elon Musk. Musk took time, money, and many failures to build SpaceX. It will take the same to construct the AAM industry.

Short-term behaviours, aspirations, and expectations driven by SPACs will not help AAM but will probably be counterproductive. The LILM case, despite its specific facts, shows that disappointed investors, who have a short investment timeline and low-risk profile, will inevitably feel let down by AAM.

Time and the perception of time are critical elements of investment behaviour. So much so that it will be the subject of our following newsletter. See you next week.

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice. It is an opinion piece written by the author.

As always, we’d like to thank our friends at Sentieo for providing the data for this article. You can find out more at: